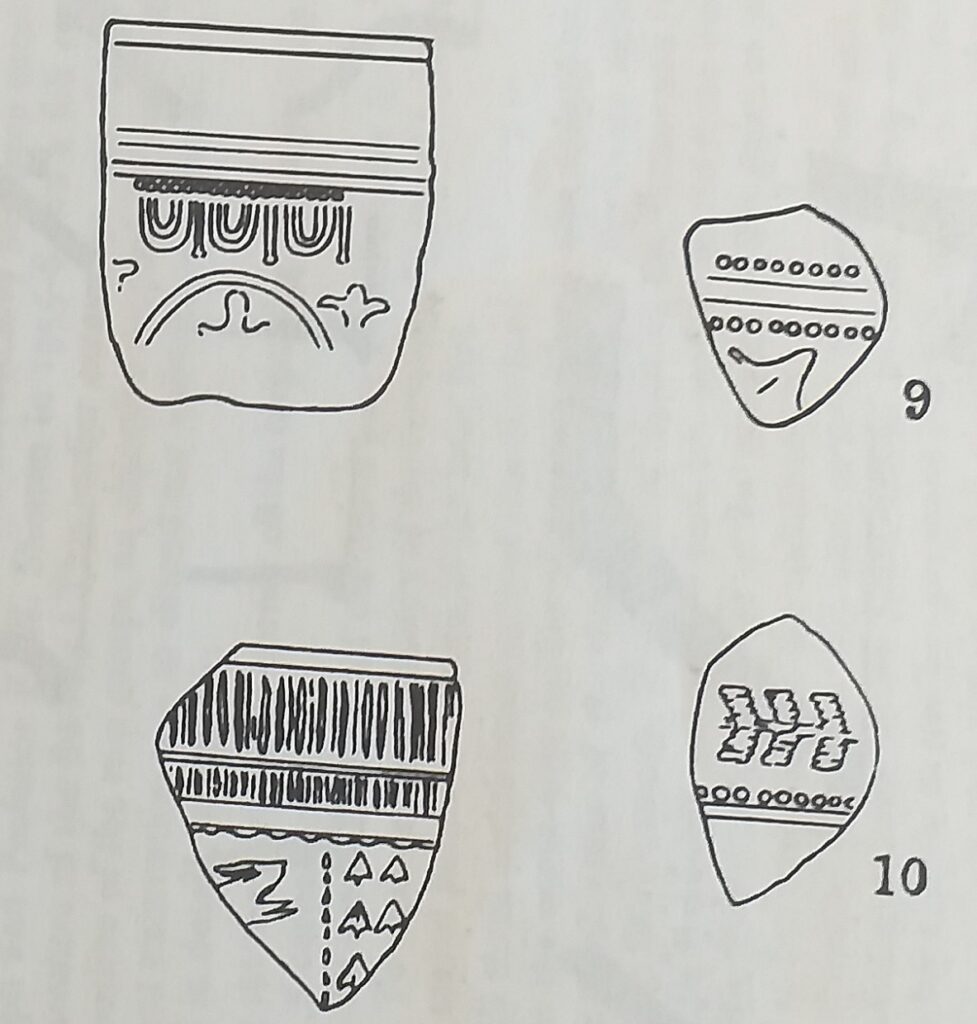

The old name for Stirchley was Strutley Street. The “ley” part usually refers to a clearing and the “Strut” part usually relates to a street, and a Roman street at that, so Stirchley was a clearing by a road. Why Stirchley was named twice though – clearing-by-the-street street – is unknown. Maybe it was to reinforce that there was a road here, for anyone who hadn’t noticed. And there definitely was, and still is, a very straight road which leads from Bournville Lane, near Stirchley Library, down to Breedon Cross, where the canal now cuts under the road. It is known that a Roman road ran through the area here somewhere, and although it’s difficult to prove, it’s widely accepted that this straight section of road is one of the only known sections of the old Roman route in the vicinity of Birmingham. Going north, the Roman fort of Metchley was uncovered near University Station, suggesting that the road passed nearby. Then, near Perry Bridge (the oldest surviving bridge in Birmingham) a Roman pottery kiln was excavated in Mr. Jolly’s back garden (Mr. Jolly kept finding Roman pottery sherds when digging his vegetable patch), so it is likely that this is near to where the road crossed the broader waters of the River Tame.[1] It also shows that the road carried ancient, locally-made, pottery along its route. North again, at Sutton Park, you can tread Roman footsteps on a surviving surface of the road there. This road was Ryknield Street, but spelt in a multitude of ways over the years, such as:

- Yknielde Strete

- Ikenildestret

- Rikenildstrete

- Ekelingstrete

- Ikelyngstreyte.[2]

The whole road was approximately 112 miles long. If we attempted to walk its route from Breedon Cross to the River Tame in Perry Barr, it’s about seven miles.

Excavations of surviving parts, such as in Sutton Park and near Wall (by Lichfield), show that these sections of Rycknield Street were constructed in a much less substantial way than other Roman roads, such as nearby Watling Street. This may have been because it was a less important route, or a quick construction due to need. Also, excavations suggest there was no older route which the Romans’ utilised beneath the stones and gravel of Rycknield Street, whereas other roads were sometimes placed on top of Neolithic or Iron Age roads. Rycknield Street is thought, inconclusively, to have been constructed in about the first century AD. This was around the time of the emperor Claudius.[3]

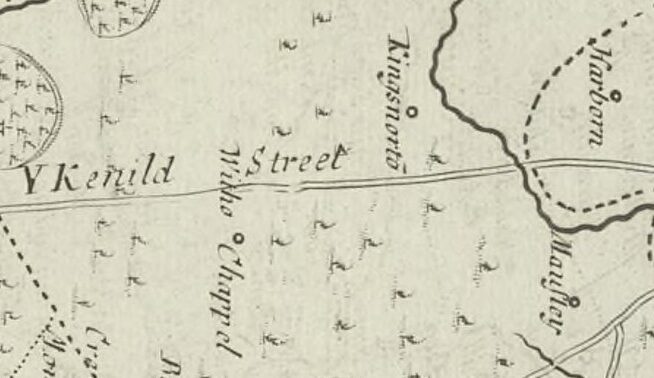

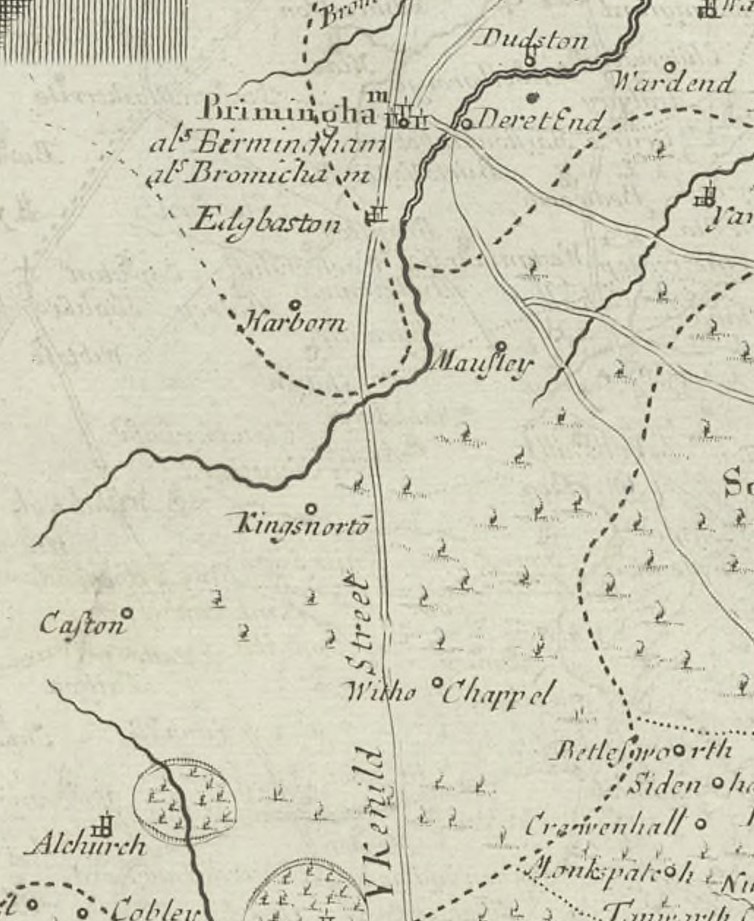

Ryknield Street has attracted much speculation about its route for hundreds of years. Robert Morden’s 1695 Map of Warwickshire drew the line of YKnield Street cutting through the Forest of Arden near Kings Norton, northward through where the clearing of Strutely Street would have been, and on towards “Brimingham”. Although depicting only one major road, by this time multiple routes had cut through the area to confuse any old knowledge of the ancient route, but the map shows that tales of the old road sparked imaginations. William Stukeley’s book Itinerarium Curiosum [Curious Itinerary], written in 1725, also described a route of the road for curious readers, but this route is widely considered incorrect. In 1785 the first historian of Birmingham, William Hutton, a local bookseller, noted a different route again.[4] Hutton’s route was so respected that roads along it were renamed Icknield Street despite, since his time, it being realised that they were unlikely ever part of the Roman road.

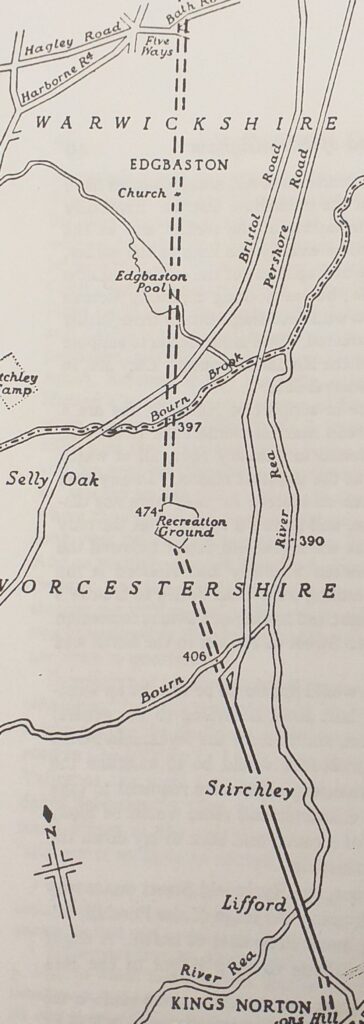

The first person to use more modern historic and archaeological methods to map the route of Ryknield Street was Benjamin Walker in 1936. He dismissed Hutton’s route, proposed his own route, but declared that any suggestion, even his own, was mere speculation. Both Hutton and Walker, though, included the Stirchley stretch as one of the only near certain sections of the road in the district.

On walking Ryknield Street north through Stirchley, you would emerge from the vicinity of Kings Norton and cross the River Rea at Lifford (the word “ford” denotes a crossing point), then continue northward to where Bournville Lane, and Stirchley Baths and Library are today, then cross the Bourn.

References

[1] H. V. Hughes, ‘A Romano-British Kiln Site at Perry Barr, Birmingham’ (1959) in Archaeological Society, 77, pp. 33–39.

[2] A. Mawer and F. M Stenton, The Place-Names of Worcestershire (Cambridge Uni Press, 1969), p. 2.

[3] Benjamin Walker, ‘The Ryknield Street in the Neighbourhood of Birmingham’ (1936) in Transactions of the Birmingham & Warwickshire Archaeol. Soc., 60, p. 42-55.

[4] William Hutton was a bookseller and paper maker on High Street whose eighteenth-century bookshop was, with pleasant symmetry, on the site where Waterstones now resides.